Geoeconomics and “De‑Risking”: The German Mittelstand Dilemma

Germany’s new geoeconomic turn toward “de‑risking” from China collides directly with the structural realities of its Mittelstand, which depends on deeply embedded global value chains and the Chinese market for competitiveness, innovation, and growth. The core dilemma is that genuine risk reduction requires diversification and sometimes retrenchment. However, for many Mittelstand firms, the very same China exposure that Berlin now frames as a vulnerability has long been a key source of resilience and technological upgrading. This tension is sharpened by the fact that, even amid political calls to reduce dependence, China has once again become Germany’s top trading partner in 2025, with bilateral trade of around €185.9 billion in the first three quarters alone. As a result, de‑risking is less about a clean break from China and more about navigating a fragile balance between economic interdependence and strategic vulnerability.

Geoeconomics and the rise of de‑risking

Geoeconomics refers to the application of economic instruments—such as trade, investment, finance, and technology policy—to achieve strategic and security objectives. For the EU and Germany, the experience of Russia’s weaponisation of gas supplies and mounting concerns over Chinese economic coercion have pushed “economic security” and “de‑risking” to the centre of policy. The EU’s 2023 Economic Security Strategy explicitly identifies four risk areas—supply chains, critical infrastructure, technology security, and economic coercion—framing de‑risking as a way to reduce dangerous dependencies without embracing full decoupling.

In this context, Berlin’s China Strategy, adopted in 2023, characterizes China as a “partner, competitor and systemic rival” and urges firms to avoid excessive dependencies, particularly in critical sectors and technologies. The aim is not to shut the door on China, which remains Germany’s largest single trading partner, but to rebalance exposure so that shocks—from sanctions to blockades or coercive trade measures—do not translate into systemic vulnerability.

Mittelstand: backbone under pressure

The Mittelstand – roughly 3.8 million small and medium-sized enterprises – accounts for over 99% of German firms and a large share of employment, innovation, and exports. Even though large corporations dominate headlines, SMEs generate about half of German export sales, with manufacturing‑oriented Mittelstand firms particularly embedded in global value chains. Europe remains their primary market, but Asia—especially China—has emerged as a major outlet: China alone accounts for about 14% of Mittelstand exports and around 7% of their imports, making it one of their top non‑European trade partners.

These firms are often family‑owned, capital‑constrained, and heavily specialised in narrow market niches, which shapes their risk calculus. On the one hand, long investment horizons, conservative financing, and close customer relationships make them structurally risk‑averse. On the other hand, once they commit to a market like China, sunk costs in plants, distribution, and local partnerships create powerful incentives to stay, even as geopolitical risks rise. This tension lies at the heart of the Mittelstand de‑risking dilemma.

The China exposure puzzle

Germany’s trade with China has grown by more than 900% since 2001 – from roughly 27 billion USD to around 273 billion USD in 2024 – with Germany accounting for about one‑third of total EU–China trade. For many Mittelstand firms, China is simultaneously a key sales market, an innovation hub, and a crucial production base, especially for components, machinery, and intermediate goods. Statistical monitoring shows that out of more than 14,300 eight‑digit product groups, a bit over 200 have a Chinese import share above 50%, and 77 of these have maintained such high shares for five consecutive years—indicating persistent dependencies in a relatively narrow but strategically sensitive set of inputs.

Contrary to political rhetoric, there is so far little evidence of broad‑based de‑risking on the import side. Germany’s total imports from China have dipped slightly in value, but the number of product groups with potentially critical dependency and the average import share of China in those categories have actually risen marginally. In roughly 45 of the 77 persistent dependency product groups, China’s share increased further in 2024 compared to the 2020–2023 average, suggesting that for some niches, the opposite of de‑risking is occurring. For Mittelstand suppliers relying on highly specialised Chinese inputs, diversification is often costly or technically difficult, which blunts the impact of political exhortations to “spread risk.”

On the export side, many German firms are moving towards an “in China, for China” model by deepening local manufacturing and R&D in China to serve the Chinese market while trying to insulate operations from geopolitical shocks. Rather than exiting, they are embedding themselves more deeply into Chinese ecosystems, reasoning that a strong local footprint is the best hedge against tariffs, sanctions, or supply disruptions. For the Mittelstand, this strategy can preserve market share but also increase asset and technology exposure to a state that Berlin now labels a systemic rival.

Policy-driven de‑risking vs firm-level incentives

Berlin has started to translate its China Strategy into concrete instruments, including tighter investment screening, export controls on certain dual‑use or advanced technologies, and more restrictive investment guarantees for projects in China. Between January and August 2023, government investment guarantees for China projects fell to around 51 million euros, compared with almost 746 million euros in 2022, signalling a deliberate attempt to curb state‑backed risk‑taking. At the EU level, the emerging economic security doctrine stresses targeted de‑risking in critical raw materials, semiconductors, and other strategic technologies, coupled with anti‑coercion tools to deter hostile trade measures.

For Mittelstand firms, however, the calculus is more prosaic: margins, market access, and technological upgrading. Surveys and interviews indicate that many medium‑sized firms have begun to hedge by:

- Localising production in China to reduce cross‑border exposure and logistical risk.

- Incrementally diversifying suppliers within Asia, for example, to Vietnam or India, where feasible.

- Ring‑fencing sensitive technologies in Europe while offshoring more commoditised production steps.

Yet these adjustments are typically gradual and opportunistic rather than a dramatic pivot away from China. Family‑owned owners prioritise continuation of the business across generations and fear that aggressive de‑risking—closing plants, abandoning relationships, or duplicating capacity—will erode competitiveness in the very markets that underpin their long‑term survival.

Navigating the dilemma

The German Mittelstand now operates in a world where markets and security are tightly intertwined, but the tools and timelines of geoeconomic policy do not always align with firm-level constraints. Policymakers want faster diversification and reduced exposure in critical sectors, while Mittelstand owners seek predictability, cost control, and access to growth markets after years of sluggish domestic demand. Statistics on persistent import dependencies and continued investment in China show that, so far, structural economic incentives have outweighed the nascent geoeconomic doctrine.

Resolving this tension requires more than exhortations to “de‑risk.” It implies targeted state support for diversification (for example, through export credit, investment guarantees, and infrastructure for alternative markets), better intelligence on product‑level risks, and a more nuanced regulatory environment that protects security interests without forcing SMEs into abrupt or unilateral disengagement. For the Mittelstand, the challenge is to internalise geopolitical risk as a core business variable—treating location and partner choices not only as commercial decisions, but as strategic ones in an era where geoeconomics is no longer an abstract concept but a daily operating condition.

Photo by Bernd Dittrich on Unsplash

The World in Focus: Highlights from Foreign Affairs’ Best Books of 2025

2025: A World Without Resolution

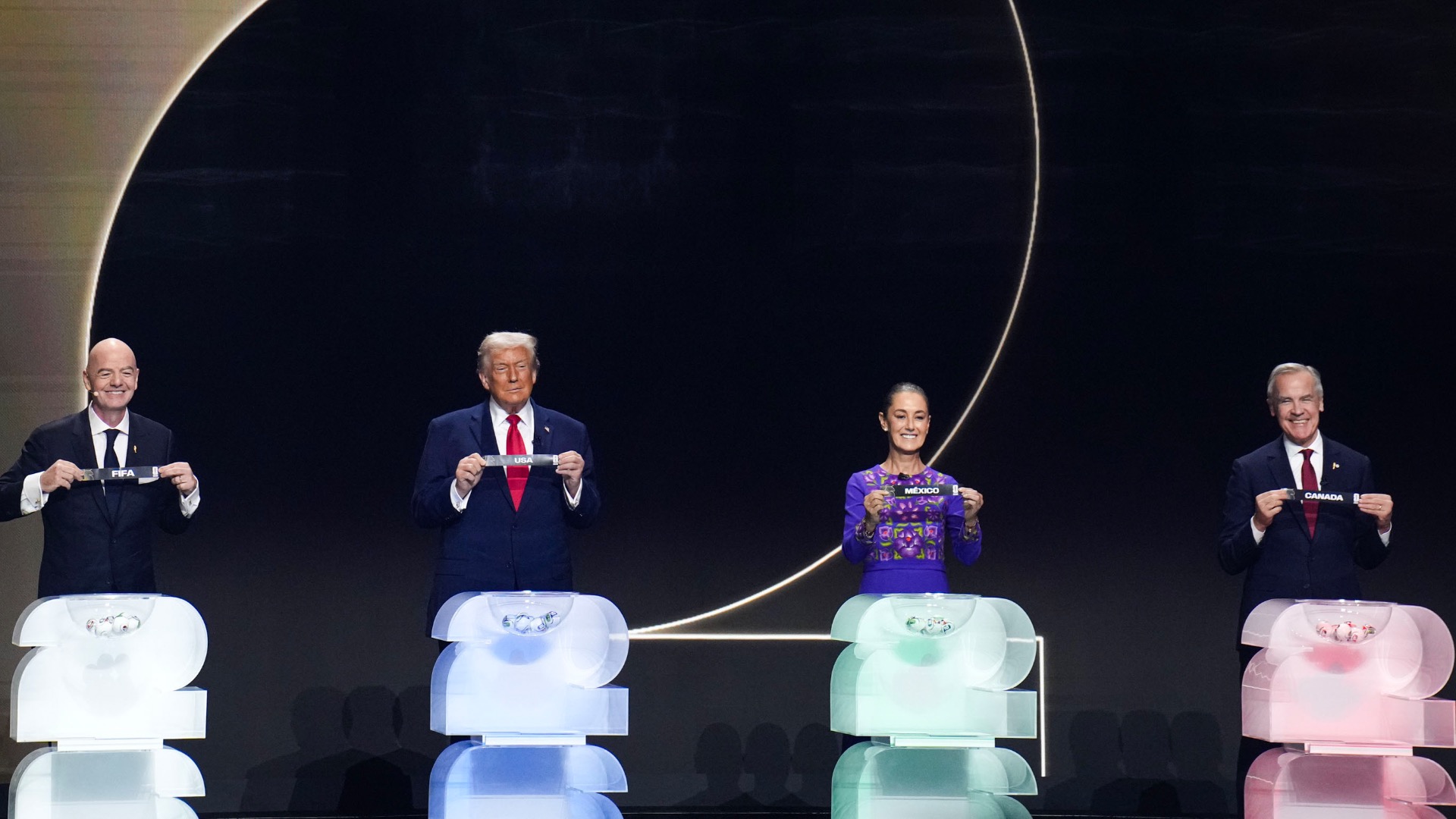

The U.S.-Venezuela Limited War of 2025: A Legal and Strategic Assessment