Energy Security After Ukraine: Has Europe Traded One Dependence for Another?

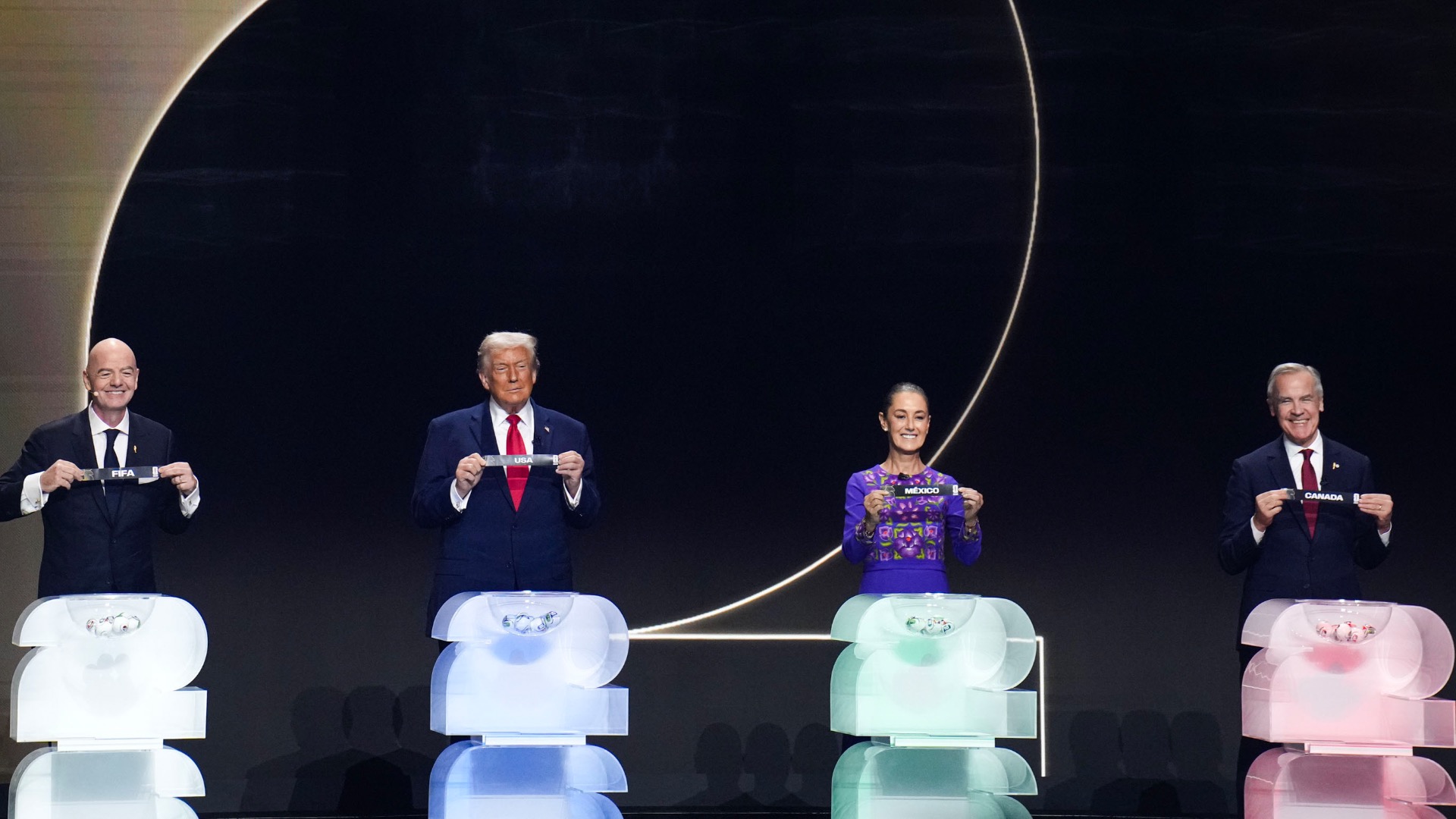

On July 27, 2025, the EU pledged to purchase $750 billion worth of U.S. energy products—LNG, oil, and nuclear fuel—between 2026 and 2028. In 2024, the EU imported just about $70 billion worth of energy products from the U.S. To meet the set target of $750 billion, the EU would have to triple its current energy imports annually. However, according to Article 194(2) of TFEU, the EU cannot impose a direct obligation to purchase energy from the United States. Therefore, this deal appears less about energy and more a strategic gesture to avert looming U.S. tariffs, thus raising critical questions about the EU’s autonomy in energy policy.

For years, the European continent relied on Russian pipeline gas, which accounted for nearly 40% of its total gas consumption in 2021. However, the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 compelled Europe to look for alternative energy sources immediately, which led to rapid diversification towards American liquefied natural gas (LNG). By 2024, Russian pipeline gas deliveries declined to just 11%. According to Eurostat, in the first half (H1) of 2025, 55% of EU LNG and natural gas imports were from the United States, while 17% were still from Russia.

From Russian Pipelines to American LNG: A New Dependence?

The transformation from Russian pipeline gas to American LNG was underpinned by high-level political commitments. In March 2022, the U.S. and the EU issued a joint statement, in which both parties agreed to „reduce Europe’s dependency on Russian energy“ and the U.S. committed to providing „additional LNG volumes for the EU market of at least 15 bcm in 2022 with expected increases going forward“. Its goal was to assist Europe in achieving energy security amid the crisis and support the EU’s REPowerEU goals to end dependence on Russian fossil fuels by 2027. Similarly, the European Commission also pledged to expedite regulatory processes for LNG import infrastructure. To that end, it established an EU Energy Platform to coordinate demand and facilitate long-term contracting mechanisms.

At first glance, this shift appeared to be a pragmatic necessity, i.e., decoupling from an aggressive authoritarian regime while maintaining energy flows. However, it has become increasingly clear that Europe has just replaced one external dependency with another, which under Trump’s leadership is even more unreliable. American LNG now accounts for more than 60% of Europe’s gas imports, posing new risks related to transatlantic shipping lanes, US export regulations, and market volatility. In 2025, the International Energy Agency (IEA) also warned that „excessive reliance on a small number of suppliers“ poses distinctive geopolitical risks.

Kerstin Andreae, Chairwoman of the German Association of Energy and Water Industries (BDEW), told Diplomacy Berlin, „If Russian gas volumes are replaced by US LNG, this would amount to around 40 bcm annually—roughly €12–14 billion per year at current prices. Even if the ratio between the raw materials in energy imports is unclear and the total of €750 billion were to be interpreted as contracted energy volumes, this would result in approximately €180 billion for natural gas over 15 years“.

These figures raise serious questions about the sustainability and credibility of the proposed agreement, as they do not align with Europe’s actual gas demand or historical import levels. On one hand, the deal appears largely symbolic, more about geopolitics than energy logistics. On the other hand, it also signals an overcommitment to energy volumes that exceed Europe’s energy requirements or infrastructure capacity, carrying substantial financial and strategic risks. Either way, Andreae’s caution highlights a more serious problem: the agreement runs the risk of tying Europe into long-term agreements that could go against its own energy sovereignty and decarbonisation objectives.

Green Transition: Aspirations Amidst Fragmentation

The energy crisis also sparked unprecedented political agreement to accelerate Europe’s decarbonisation. In 2022, the European Green Deal and the REPowerEU plan set ambitious goals, such as a 55% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 and net-zero emissions by 2050. Different renewable energy sources like wind and solar capacity expanded rapidly with the support of €350 billion in investments from the European Defence Fund and private capital.

Yet, there exist deep internal divisions among EU member states over the pace and method of the transition. Countries such as France and Germany advocate for nuclear energy, viewing it as a low-carbon baseload source. German Chancellor Friedrich Merz is pro-nuclear and considers abandoning nuclear energy as a “serious strategic mistake”. France depends on nuclear power for more than 70% of its electricity consumption, but opposes plans to phase out its reactors prematurely.

On the other hand, countries like Denmark, Ireland, and Austria are still adamantly opposed to nuclear power and are pushing for energy efficiency and renewable energy instead. This discrepancy slows down important investments and regulatory harmonisation, making it more difficult to adopt coherent energy policies for the entire EU. A failure to resolve these issues, along with ensuring robust energy storage and grid modernization for renewable energy, could potentially translate to supply volatility and increased prices.

Broader Implications for European Strategic Autonomy

Europe’s quest for strategic autonomy continues to be a central theme in its defence and energy discourse. However, the recent events draw attention to persistent limitations. Europe’s strategic energy autonomy is aspirational but incomplete, as evidenced by its over-reliance on American LNG and internal conflicts over energy policy. Although it provides short-term resilience, it also exposes Europe to external challenges.

Meanwhile, the Green transition represents Europe’s long-term vision, but is marked by internal conflicts and technological difficulties. To ensure strategic autonomy, the EU must build interconnectivity into its energy systems, support technological innovation in storage and renewables, and balance diverging national interests into cohesive policies. This includes diversifying supply chains, investing in eco-friendly technologies, and balancing external partnerships with internal resilience.

As Andreae puts it, „The fundamental principle is to further diversify gas supplies to avoid concentration risks with individual supplier countries“. Ultimately, Europe’s energy transition is less about eliminating dependencies and more about strategically redistributing them in a multipolar world.

The World in Focus: Highlights from Foreign Affairs’ Best Books of 2025

2025: A World Without Resolution

The U.S.-Venezuela Limited War of 2025: A Legal and Strategic Assessment