Efficiency First, Not LNG: Rethinking the EU–US Energy Agreement

A Deal at Odds with Europe’s Climate Path

The recently announced EU–US energy agreement, under which Europe would import roughly $750 billion of US energy products between 2026 and 2028, raises difficult questions. Will such large-scale LNG and oil imports strengthen Europe’s energy system or undermine its Green Deal goals, energy transition, and strategic autonomy?

LNG vs. Efficiency First

The EU-US LNG import deal poses a serious challenge to the EU’s long-term decarbonization target. The path followed so far to reduce Europe’s energy demand is to increase the production of renewable energy, either to diversify electricity production and to increase the end uses of clean energy. However, there are various ways to reduce energy demand, whether in terms of primary energy (the fuel sources) or final energy (the energy used by consumers). In this regard, the most critical measure is to improve energy efficiency, as outlined in various legislations, including the most prominent recast Energy Efficiency Directive.

The principle of Energy Efficiency First, embedded in both EU and national laws, establishes the basis for prioritizing public financing (or public/private) in demand-side investments rather than supply-side projects. Despite shifting energy source, increasing LNG imports risks moving Europe in opposite direction. It would lead to increased energy use, which in turn would require more public investments (new terminals, new floating storage and regasification units (FSRUs), upgrading of existing ones), which can be used to finance energy efficiency actions and refurbishments of the building stock.

Several cost-efficiency analyses funded by the EU, including Regio1st demonstrate that financing structural reduction in energy demand, especially in buildings (majority regions) is more efficient than financing new gas terminals to import fuel. Therefore, this evidence should be carefully considered before any new supply-side infrastructure investments are approved.

Energy Security or Market Lock-in?

Although increasing LNG imports from the US could, in theory, provide short-term, they come with significant and unpredictable costs. Such investments could indirectly jeopardize EU decarbonization process, where clean energy investments are already underway. These contradictory signals of expanding fossil fuels could potentially discourage investments in renewable energy, while also contributing to market uncertainty.

Considering 2040 EU climate target, and Member States’ National Energy and Climate Plans, it is Imperative to reduce dependence on gas. Therefore, the current increase in LNG imports, coupled with the danger of further lock-in cannot be justified. Furthermore, the end-use of LNG beyond electricity production can potentially increase household costs during coming winters. This would not only aggravate energy poverty but also contradict the spirit of Social Climate Plans.

Strategic Autonomy at Risk

The EU’s climate leadership remains credible as long as climate change holds central position in public discourse. However, the protection of strategic autonomy is equally important, considering the increasing share of renewables in electricity production, and their role in key industries such as trains powered by wind energy, increasing sales of heat pumps, and rooftop solar panels.

What is missing, however, is policy alignment with real energy needs. The challenging task is not to generate more energy for future electrification, instead, it is effective absorption, smart storage, and allocation of abundant renewable electricity already being produced. System stability is therefore less about increasing supply and more about managing the flow of electricity to end-users without curtailing existing renewable energy production. Here, we should note that several renewable energy-producing countries have already faced curtailment over the past three years. Therefore, the large-scale imports of LNG, oil, and nuclear fuels from the US to EU accounting to 250 billion US Dollar (215 billion euros) annually for three years are neither required, nor justified.

The data from Eurostat highlights that EU’s monthly average has been 30 billion Euros, totaling roughly 360 billion euros annually, except the price spikes in 2022. This is about 1.7 times larger than the projected US energy imports, but it includes everything, including oil, natural gas, LNG and nuclear fuels.

According to Eurostat data, the largest portion of EU’s imported energy costs comes from oil. However, the data also indicates a downward trend in oil demand. Around 15% of EU oil imports are from US (about €36 billion annually), but the increasing use of electric vehicles, and heat pumps in buildings along with other efficiency measures will further accelerate this downward trend.

The second major category of energy imports is natural gas. About half of recent LNG imports now come from the US, amounting to €20–28 billion per year. It is true that LNG replaced pipeline gas, but the overall gas demand in the EU has fallen by 20% since 2021 because of energy efficiency improvements in both buildings and industry. The 2025 brief increase in LNG imports can be attributed to unusual cold winter, which resulted in gas storage levels dropping below the seasonal average. However, this was a short-term effect, rather than a long-term trend.

Moving forward, the gas demand will further decline in both the buildings and power sectors (replaced by renewables). There is already ongoing debate regarding LNG overcapacity in Europe, even before accounting for the proposed increase in US imports.

Conclusion

Overall, the scale of energy imports from US is both unrealistic and unjustified given current and projected energy demand trends, especially in the context of the EU’s Green Deal ambitions and the RepowerEU Plan. These imports will redirect necessary financial investments away from energy efficiency, renewable energy expansion, and infrastructure upgrades. Furthermore, it would also create long-term dependencies which could extend far beyond the proposed three-year period. At best, this deal represents a reckless misallocation of scarce public funds; at worst, it directly undermines the EU’s commitments to energy efficiency and climate objectives.

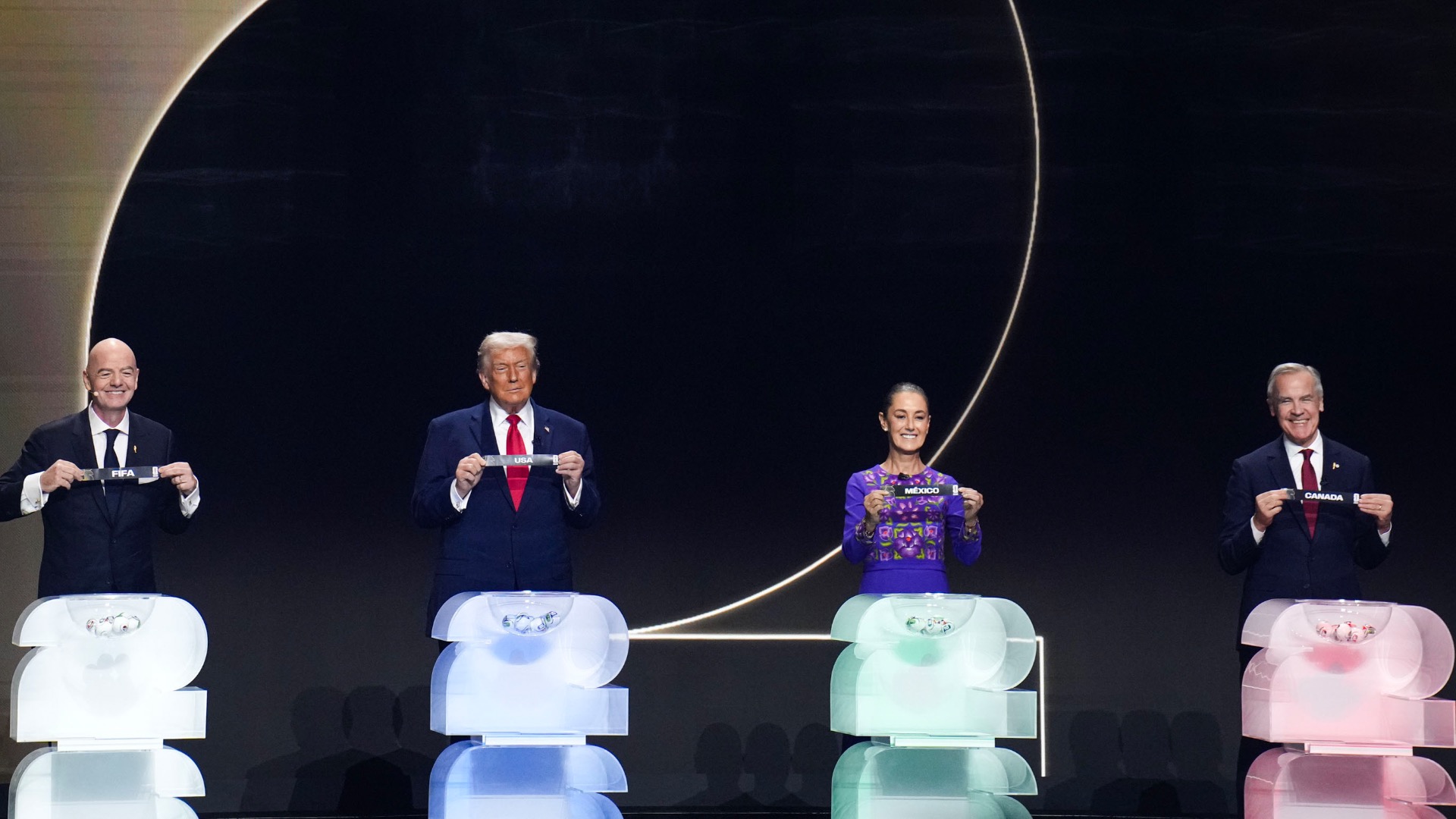

© European Union, 2025. Photo: Fred Guerdin / EC – Audiovisual Service. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International.

The World in Focus: Highlights from Foreign Affairs’ Best Books of 2025

2025: A World Without Resolution

The U.S.-Venezuela Limited War of 2025: A Legal and Strategic Assessment